Published October 17, 2022 • 5 Min Read

This report was first published by RBC Economics on Oct. 12, 2022.

- In previous work, we projected a moderate recession for Canada’s economy in 2023. We now believe this downturn will arrive as early as the first quarter of next year.

- Higher prices and interest rates will shave $3,000 off the average household’s purchasing power, weighing on goods purchases.

- And the jobless rate will near seven per cent while remaining less severe than in previous downturns.

- As debt-servicing costs increase and purchasing power declines, lower income Canadians — many already adjusting to the loss of pandemic support — will be hit hardest.

- The bottom line: The pain of the upcoming recession won’t be distributed equally among Canadian businesses and households. The manufacturing sector will likely be among the first to pull back while some high-contact service sectors like travel and hospitality could prove more resilient than in a “normal” historical recession.

Signs of strain are emerging as interest rates rise. Cracks are forming in Canada’s economy. Housing markets have cooled sharply. Central banks are in the midst of one of the most aggressive rate-hiking cycles in history. And while labour markets remain strong, employment is down by 92,000 over the last four months.

And the pressure is still building. While the Bank of Canada is expected to lift the overnight rate to four per cent, the U.S. Federal Reserve will likely hike to between 4.5 and 4.75 per cent by early 2023. These factors will hasten the arrival of a recession in Canada — which we now expect to start in the first quarter of 2023 (one quarter earlier than our previous projection).

What happens next will depend on a range of factors, with interest rate increases the most significant among them. Central banks will be reluctant to throw in the towel on rate hikes before they are confident that inflation will slow sustainably. We expect the Bank of Canada to pause its rate-hiking cycle in late 2022 followed by the Fed in early 2023. But that’s contingent on inflation pressures easing. More stubborn inflation trends over the coming months could yet prompt additional hikes, and a potentially larger decline in household consumption and a deeper recession.

Jobs will be lost and lower-income Canadians will be hardest hit

As it stands, the labour market is the tightest it’s been in decades. An excess of job openings and a scarcity of workers will protect against a major spike in unemployment in the very near-term. The jobless rate will still rise, but we expect longer job search times for the unemployed, and hours cut for the employed at first.

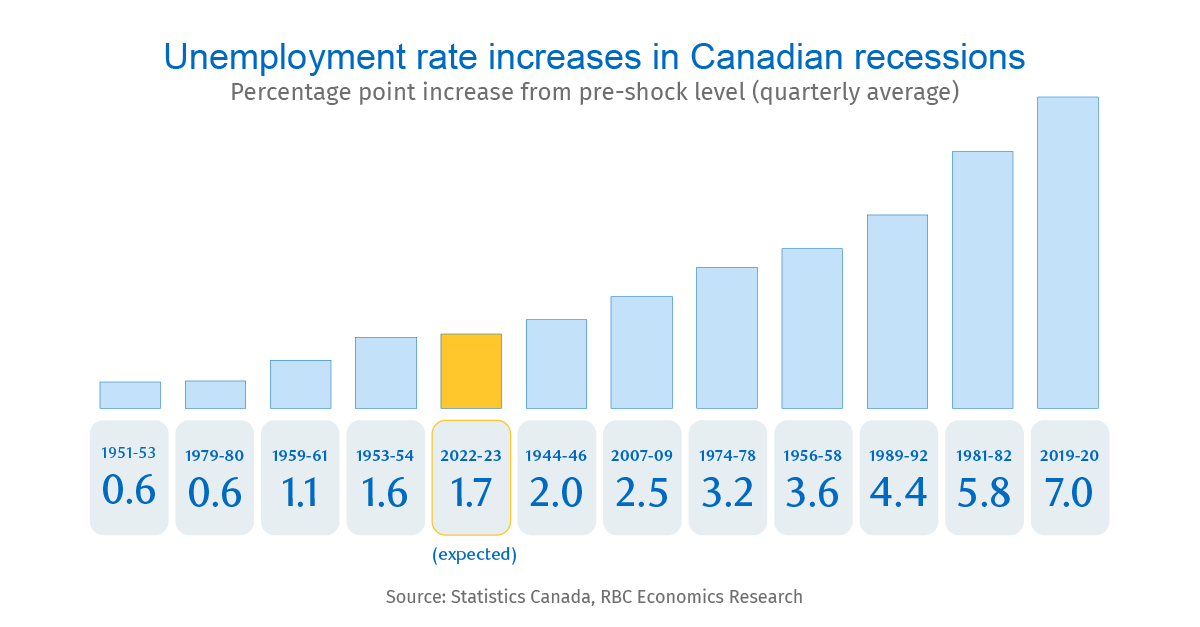

More outright layoffs will follow, and we expect the weakening in the economy will push the jobless rate close to seven per cent by the end of 2023 — up almost two percentage points from lows of 4.9 per cent in June and July. This is slightly higher than our previous forecast but still low relative to previous downturns.

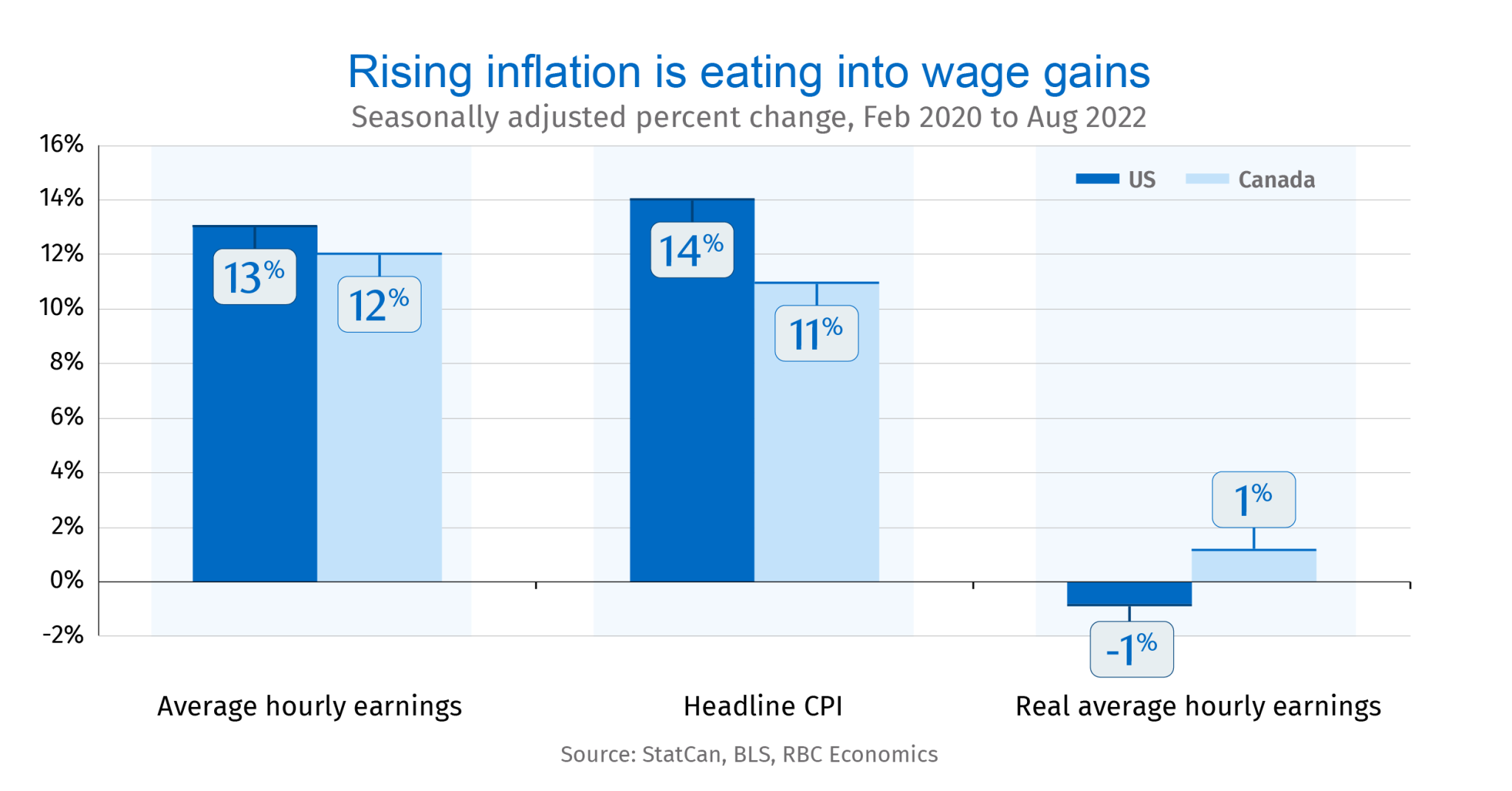

That said, households are already feeling the squeeze of economic headwinds. Rising inflation and higher borrowing and debt servicing costs are expected to shave almost $3,000 from average purchasing power in 2023. And while drum-tight job markets have pushed wages higher, it hasn’t been enough to offset these losses. This will weigh most heavily on Canadians at the lower end of the wealth spectrum, particularly those whose disposable income has faded alongside pandemic support.

A (relative) bright spot: travel and hospitality

The pain of the upcoming recession won’t be distributed equally among Canadian businesses either. Housing markets have already corrected lower. And the manufacturing sector looks poised to soften as spending on physical merchandise cools, particularly in the U.S., the world’s biggest consumer market and destination for 75 per cent of Canadian exports (65 per cent of which are “manufactured” products). In Canada, despite still-strong manufacturing output, surveys have already flagged deteriorating sentiment among businesses in that sector.

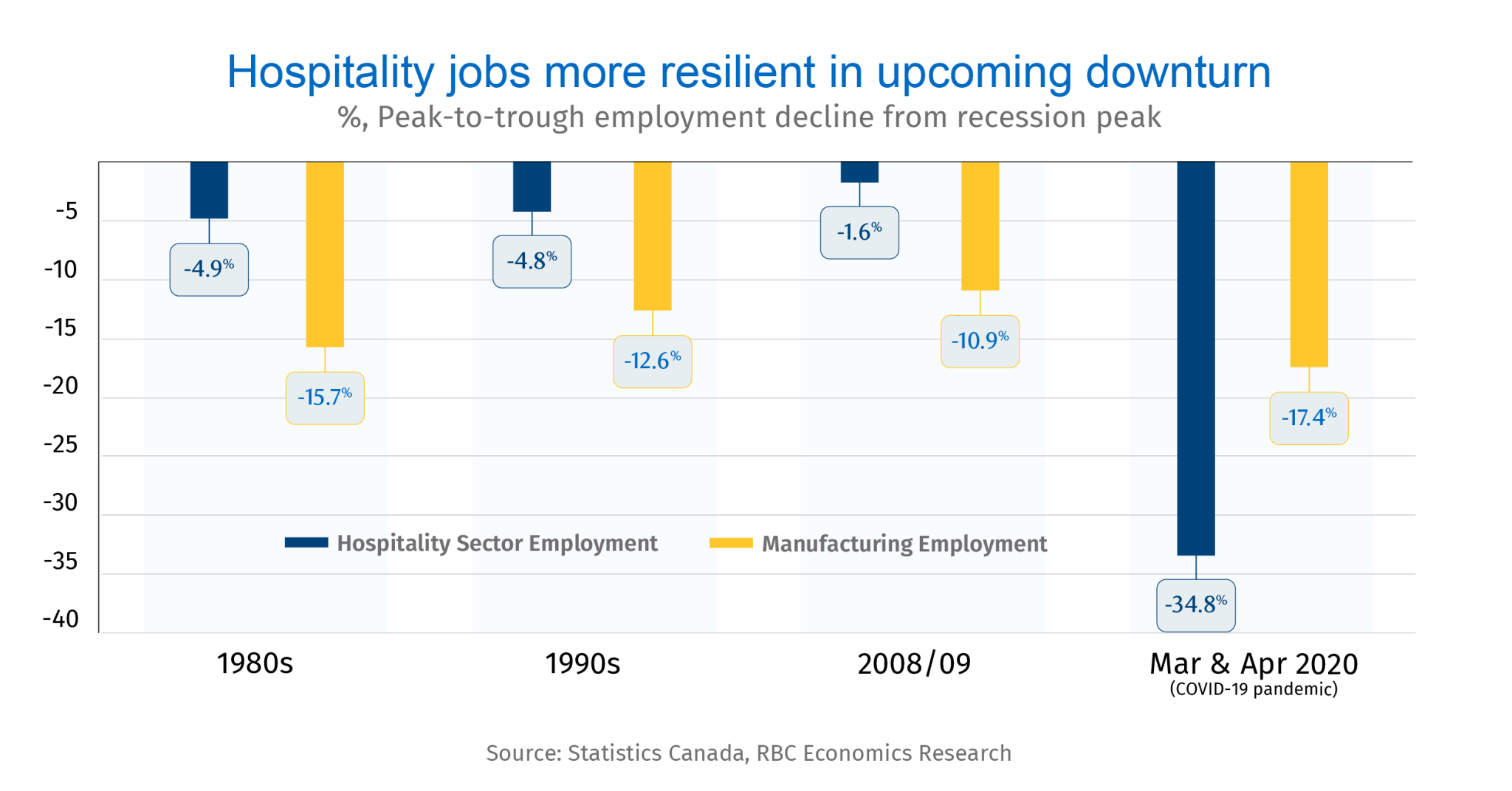

While they won’t escape unscathed, the travel and hospitality sectors — among the hardest hit by COVID-19 restrictions — could be more resilient than in past downturns. Resilience in the broader services sector compared to goods producing industries like manufacturing wouldn’t be a new phenomenon. Public-sector services jobs like teachers and healthcare workers typically decline less (if at all) in recessions. That’s also been true of the professional, scientific and technical services jobs — the largest source of employment growth from pre-pandemic levels (+17 per cent). But in the accommodation and food services sectors, where recessions typically have a more significant impact on spending, job losses are usually a lot smaller than in manufacturing. And this time, there remains lingering demand for travel and hospitality services after two years of pandemic lockdowns. That will limit a pullback in these sectors in 2023.

Travel and hospitality business will likely be among the most hesitant to resort to layoffs. Indeed, employment in accommodation and food services was still running 15 per cent below pre-pandemic levels in September. That’s three times the average decline in recessions dating back to the 1980s. That means businesses are already staffed at levels below what you would expect in a major economic downturn. As a result, they’ll be less likely than “normal” to resort to layoffs.

Find the RBC Economics forecasts for Canada and the U.S. at rbc.com/economics.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic trends and is responsible for projecting key indicators on GDP, labour markets as well as inflation for both Canada and the US.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Share This Article